Moving On

Like many of you, as much as I love my country, I need a break from an America that seems more unhinged every day. She’s like a spouse who’s suffering a mental collapse and has become unrecognizable—even scary—after years of marriage. And like investing in therapists to help an unstable spouse, eventually you have to move on to save what you can: yourself. In much the same manner, I feel I have written what I can in the moment to help my readers understand our country and have offered as many suggestions and remedies I can to promote change, or at least to allow us to cope—to hold our collective breath without turning blue, or worse. That said, I do not intend to wither on the vine and I hope you don’t either, even though somedays withering sounds masochistically inviting.

A tipping point when Americans have finally had enough of the greed and cruelty emanating from the White House may come sooner than we think. Most of the world has already written off our dear leader as a charlatan and grifter. They know they only have to patronize him for a few more years, which in many cultures is like a long weekend. I have no doubt that Trump will go too far; his sociopathy is rabid. His administration has no stop button. Its insatiable appetite for power and money and vengeance is inherently unstable and will result in either implosion or explosion. The physics of the conditions are undeniable and unstoppable; the energy fields created by these behaviors produce so much dissonance as to inevitably cause spontaneous destruction, also known as a meltdown. As Sun Tzu, the sixth century BC Chinese military general would certainly agree, the best way to defeat an adversary is to enable them to defeat themselves—maybe even cheer them on. It appears that America’s adversaries, both old and new, understand this strategy well. Trump believes he is the king while other world powers view him as a mere pawn.

As resilient as our country has been thus far, its continued abuse is clearly unsustainable. How many more little girls must drown in flash floods before we realize that hundred year floods are now every year floods, and that weather forecasters and warning systems are essential in the world of climate change? If that deadly debacle in Texas doesn’t break your heart and slap the MAGA hat off of your head, what will? Regardless of these now frequent catastrophic events, if we don’t get off fossil fuels none of these events and our many other issues will matter anyway. Without long term thinking, eventually there is no short term. I take some morbid comfort in the notion that even if we can’t fix our mess with the tools of democracy, Nature will cleanse us of this dirge-worthy era. She always prevails.

Of course, such damage is potentially catastrophic to us all, regardless of our many and varied persuasions—political and otherwise. For the MAGA crowd, those red caps may become toxic fire starters someday soon. For America, it will not be a matter of recovering empire; rather, we will be forced to re-imagine an America as a lesser version of its former self, both domestically and (especially) internationally.

Ancient historians like Polybius would suggest mob rule (ochlocracy) is next. Such is the nature of the life cycle of empires. In spite of advances in technology and knowledge, human dispositions and predilections have proven stubbornly resistant throughout human history. Our weaknesses are—paradoxically—durable. In any event, I know it will remain possible to find a sense of tranquility through the many tools of transcendence I have outlined in my previous posts. I hope you consider them elements of inspiration and healing in your virtual emergency go-bag. If you would like to access those posts, go to ameritecture.com and click on the “Spiritual” collection.

As for moving on, my next project—a book—will be my fourth and likely my last, which means you won’t hear much from me for the foreseeable future; I expect your Sunday morning inbox will survive. I am stepping back from the moment to take a broader view at a higher altitude. This book should offer me an oar to paddle off into the sunset. A story that will hopefully provide essentials to consider in re-imagining a new America. As the great American documentarian, Ken Burns, recently suggested, the only thing that can change people’s point of view is a good story. “Good stories are a kind of benevolent Trojan horse. You let them in, and they add complication, allowing you to understand that sometimes a thing and its opposite are true at the same time.” Hopefully my book, tentatively titled, Atlas Flexed: Witness to Empire, will become such a benevolent Trojan horse.

The genre of this project is a mix of history and memoir that draws on a lifetime of struggle, triumph, and most of all, learning. I take inspiration for its “personal history” structure from Fintan O’Toole, a columnist for the Irish Times and professor at Princeton University whose book, We Don’t Know Ourselves: a Personal History of Modern Ireland (Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2021) began as a memoir and morphed into a national history of Ireland covering the same time period I will address in America, from the 1950s to today.

Here is the set up:

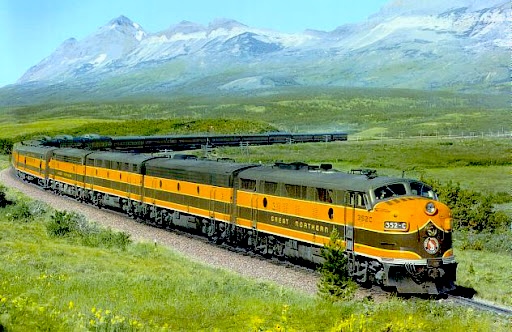

The libertarian icon and author, Ayn Rand, was wrong. At least partly wrong at the time Atlas Shrugged was published in 1957. The American Atlas of her 1950s did not shrug, as a world power it had barely been born. It was too young to express indifference let alone withdraw from the society and government her character, John Galt, loathed. In hindsight, the decade of the 1950s was the most reason-based and objective of the seven that followed, so one might argue Rand was just being prophetic. The 1950s was when America began its rise and subsequently flexed its muscles as the most powerful empire in the history of the world. In the process, it became less rational and more radical in its idealism than at any time since its founding, eventually becoming tragically disconnected from its cherished democratic republic in the 2020s. Capitalism and its natural byproduct, wealth, does tend to foster idealism to precarious ends. Posthumously, perhaps Rand was as partly correct as she was partly wrong. As it is said of philosophers and prophets: eventually they will be right—somewhere at some time.

I had the great fortune to be born at the same time as America began its ascent as a superpower—to grow and stumble and flex alongside its majesty. America’s journey in the second half of the twentieth century and the first quarter of the twenty-first was the backdrop of my life. Both America and I had great success interrupted occasionally and regrettably by stupid mistakes. How we each face our respective impending decline today is a matter of both conjecture and consternation. My decline matters to no one but me, whereas America’s matters to billions of people throughout the world. Alas, the arc of American empire and the arc of my life share a serendipitous synchronicity; we were Boomers together. I know her and she knows me.

My readers will certainly learn more about me in this book, but also hopefully reflect upon and learn more about what truly made America great, which is sure-as-hell not what is happening today. While I hold younger (under 50) Americans partly responsible for where the country is and more so where it is going, I also understand they did not live in a time where they could have known better. Their lives have been marinated in the comfort of abundance and technologies that have substantially compromised their agency. Their ignorance is understandable, but their indifference is inexcusable. At least John Galt’s indifferent shrug was principled.

I intend to inform and entertain, and maybe even inspire. In any event, the project will, as my late mother would have no doubt suggested, “keep me out of the pool halls.”

Until we meet again, cheers and stay safe.