The faces of those murdered always look the same.

Stunned with eyes wide open; the glint of wonder that once animated their eyes is lost forever. Just dark colorless empty pools of pure horror. Frozen in the moment their hearts stopped beating. There is a reason people pull their eyelids down after death: no one wants to look into those eyes. Their last question is the one none of us can answer: Why did this happen to me? An ashen pallor sets in within a few minutes after years of shaping a life they believed was theirs to live or, if murdered children, thought would someday be theirs to live. We attempt to sanitize their fate by calling them “collateral damage.” Death by greed, hate, or twisted imperial or religious idealism, all of the murdered had their lives stolen by egos larger than their own.

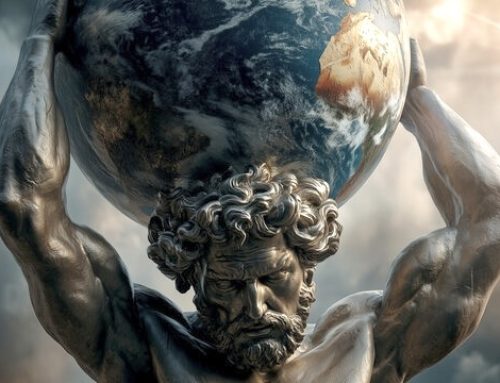

Those who decide who dies are usually men dressed in expensive suits surrounded by an entourage of other men, always in bulky black jackets with dark sunglasses. Because they certainly don’t want to die. The people who are sacrificed is justified by some twisted notion of greater good that has been carefully crafted to appeal to citizens who allow the men in suits to pursue their dreams of glory, and who escape their own culpability behind the same greater-good veil of deceit. After all, what life would they have if the grand dreams of the men in suits did not come true? Of course, the dead eyes of the sacrificed never get to answer. For them, the question is rhetorical.

This is the story of the human race told too many times to count. Most of the sacrificed die in innocence without recognition or tribute. Others die in uniform and are granted posthumous valor. But their eyes are all the same. Some are buried in national military cemeteries, others in mass graves, still others rot where they lay—a gift to the ravens. Their final resting place matters to those still living, but not to the sacrificed. Dead is, after all, dead.

Yes, violent conflict has been going on between humans for centuries. The men in suits once wore sheepskins, but still murdered with impunity. The difference today is that violent conflict is—finally—completely unnecessary. For centuries humanity endured scarcity that made conflict a means to an end of whatever was in short supply at the time. Win/lose, zero-sum was the prevailing paradigm. Today, we live in an age of abundance where there is enough of everything humans need to go around. Win/win, plus-sum. We have a distribution problem, but not a supply problem.

We live in a perpetual state of hypocrisy. On Sundays we revere the sanctity of life: “Thou shalt not kill.” The other six days we kill, or stand idly by watching. Our world religions (especially monotheistic ones) have often been at the center of the hypocrisy by playing an essential role in the greater-good scheme. Many carry signs of protest, or wave flags to draw attention to the sacrificed. Their performance accomplishes little other than to boost their self-image while assuaging their own sense of guilt. Meanwhile, we allow our tax dollars to fund the madness. As long as the death and destruction stay far away from us, we comply. Many believe that if the killing is kept elsewhere, it can’t happen here. It’s an understandable sentiment and also completely irrational. Currently in America, evil usually arrives in the form of a white man with an assault rifle. That may be just the beginning. If the dead could speak the conversation might change from an abstract concern and wishful thinking to the reality it is: to the blood-curdling horror that precedes the moment of death when those wide eyes freeze.

In a world of egomaniacs in suits and high-tech weapons soon to be driven by AI, the death of innocents has become way too easy, way too impersonal, and way too common.

Years ago, when I was a board member of the Castleberry Peace Institute, I had access to lots of research on conflict. Two truths were substantiated over and over. First, most conflict in the world is intrastate—civil wars. Second, they all end for the same reason: fatigue. The killing stops not as a result of one side’s victory; rather, as a result of the psychological and physical exhaustion of both sides. In the end, both sides lose. In the contemporary era, there is seldom ever a victory parade.

Look at the two biggest conflicts in the world today: the Russia/Ukraine war and the war between Israel and Iranian proxies. These are not resource-based conflicts. They are heritage-based conflicts where the argument is over age-old claims to territory that have been spun-up into greater-good justifications with imperial ambitions at their core. There are a number of smaller conflicts in the world that are based in scarcity (all intrastate) where distribution issues remain. But all are unnecessary. All of the underlying issues can be solved by the application of intelligence and judgment and humility and compassion and courage.

The real problem is the power-hungry egos of leaders whose compulsion to wage war resides in their own deep-seeded insecurities. Putin, Kim, Xi, Khamenei, and Netanyahu all fit the profile. For the moment, Trump does not, but only because he is currently not in power. His many followers, who chant “God, Guns & Trump!” believe it is their religious duty to cleanse America of non-Christians and those who don’t look like them or love like them. Further, they believe the immunity the Supreme Court recently granted to Trump is theirs as well; that his immunity will be their pardon. Trump’s team is already compiling their hit list of those they believe deserve retribution. I expect that yesterday’s assassination attempt in Pennsylvania will only pour fuel on that fire. The bloodlust that has infected our nation—on all sides—must be eradicated. President George W. Bush’s “axis of evil” (then Iran, Iraq, and North Korea), which many derided as hyperbole at the time is no longer abstract, it is real, and spans farther than he thought. It may soon have an anchor in America.

While we are all wringing our hands over the elections this fall, regardless of how that turns out, we must resolve to take our humanity back. I have been watching the sacrifice of innocents since the My Lai Massacre in Viet Nam. I acknowledge how durable evil is. However, it is very much in our self-interest to summon our moral fortitude to end the madness. Next time you hug someone you love, imagine how you would feel if your arms were empty—if that loved one were no longer there. That is what thousands of people experience every day in our world. Intoxicated with fantastical ambitions and addled by fragile egos, the men in suits believe our losses are justified. That is the very personification of evil. The horror present today in so much of the world may come to America soon. While not yet inevitable, our life lived in a peaceful democracy is in peril. Those dead eyes may be our own. Signs and flags are not enough.

We must demand—with our voices, labor, votes, and dollars—that the insanity of violence across the world and rising here in America ends now, before our arms are emptied, too.